Business and state in Russia: from ‘state capture’ to ‘business capture’

- Sofia Smirnova

- Dec 16, 2019

- 4 min read

Author: Gabriela Pricop

Over the last decades, we have seen an increase in the number of oligarchs, although the source of their power is rooted in the same context: a relationship with the president that leads to personal financial gain. Through controlling the major industries, ranging from oil and natural gas to steel, nickel and other essential industries, Russian oligarchs started to dominate all aspects of daily life. Shortly after, they spread to other fields, such as media and sports. But, at their core, the oligarchs gained their wealth from industry and wielded their power openly and with impunity.

On numerous occasions, Russia has been described as a ‘mafia state’ (Harding, 2010) in which state officials, oligarchs and organised criminals are all bound together. While it is true that organised crime and political power have always been interconnected in some way in both Soviet and post-Soviet Russia, the label ‘mafia state’ does not aptly reflect the precise nature of this connection today. Indeed, today’s Russia is a country of big business. The number of Russian billionaires on the Forbes list rose from 17 in 2003 to 96 in 2017, which is highly anomalous by world standards.

However, many scholars and journalists alike contend that the political influence of big business and super-rich has decreased dramatically since Putin was elected president in 2000. Thus, for Andrei Yakovlev, “relations between business and state, in a very short time span, have made a shift from ‘state capture’ model to the model of informal submission of private businesses to state interests, which can be labelled as ‘business capture’”.

Oligarchs in Russia: do they still exist?

At the 2017 Davos Forum, then-deputy prime minister Arkadiy Dvorkovich claimed that “We no longer have oligarchs. It was the concept of the 1990s. Now we have good, socially responsible businessmen who care about the country and earn money by doing responsible business”. Thus, based on this statement, Dvorkovich paints the picture of an obedient business class that operates in complete harmony with national interests, in contrast to the irresponsile “oligarchy” of the Yeltsin era.

This argument conceals, however, the complicated and still evolving nature of the relationship between the state and large companies. While the ability of large companies to engage in public politics and directly influence policy making has decreased during Putin’s years in office, this loss has, to an extent, been compensated for by the increase in their structural power - that is, the state’s dependence on their investment decisions.

While Russian officials are right to claim that today’s business leaders do not preside over the country’s politics as they did in the 1990s, an argument can still be made that the business elite in Putin’s Russia constitutes an “oligarchy” in the specific sense advanced by Jeffrey Winters and Benjamin Page: it is a narrow group of super-wealthy that dominates certain policy areas in a context of extreme wealth and income inequality.

In an article for Moscow Times, Davis Szakonyi made a clear distinction between three different groups of oligarchs in Russia, all of them fitting the definition advanced by Winters and Page, however holding different degrees of power. Firstly, there is the so called “inner-circle” which includes individuals whom Putin had long-standing relationships with: Gennady Timchenko (net worth $15 billion), Arkady Rotenberg ($2,4 billion) and Yuri Kovalchuk ($1,2 billion). The second group consists of people who come from the security sector and capitalize on these networks (Igor Sechin – CEO of Rosneft, Sergei Chemezov – CEO of Rostec). Lastly but not least, Szaknoyi identifies a third group – the “holdovers”. These are powerful business people who created their wealth thanks to their connection with previous presidential administrations (Vladimir Potanin – Yeltsin era and Ziyavudin Magomedov – Medvedem era).

Why are the super-rich still loyal?

Taking into consideration the decreased influence on policy making the super-rich have in today Putin’s Russia, one may rightfully ask: what is it that make oligarchs remain loyal to Vladimir Putin?

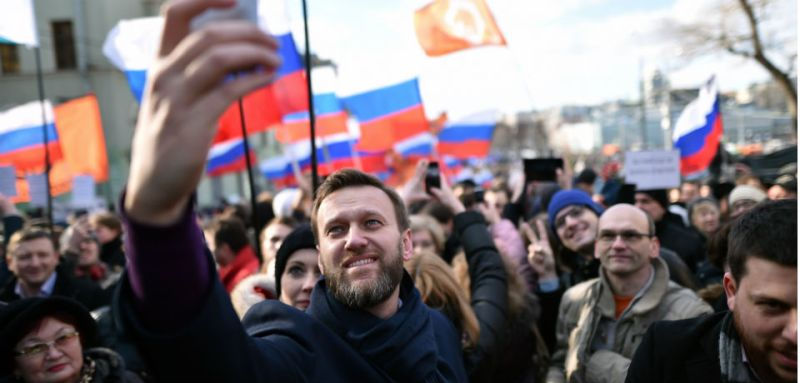

For one thing, even if Putin’s regime has not always catered to the interest of big business, the alternatives might be worse. For instance, in 2017-2018 Alexey Navalny injected strong elements of left populism into his political program, adopting slogans like “Prosperity for all, not wealth for the 0.1%” and calling for a “compensatory tax” on the oligarchs’ privatization profits. Therefore, democratization in Russia would entail an attach on big capital that would not only endanger the wealth of those business leaders with close ties to the Kremlin, but also result in stronger redistributive policies affecting large businesses as a whole. As a result, cultivating Putin’s loyalty and supporting Russia’s electoral regime is probably still a better political shell for the Russian super-rich.

Reference List:

1. Jeffrey Winters and Benjamin Page. 2009. “Oligarchy in the United States?” Perspectives on Politics 7:4

2. Andrei Yakovlev. 2006. “The Evolution of Business-State Interaction in Russia: From State Capture to Business Capture?” Europe-Asia Studies 58: 7: 1048.

3. “Russia’s Dvorkovich Optimistic About Future of Economy.” Bloomberg.com. January 24, 2018, At https://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2018-01-24/russia-s-dvorkovich-op- timistic-about-future-of-economy-video, accessed 03 December, 2019.

4. “Programma Alekseia Naval’nogo” [Platform of Alexey Navalny], At https://2018.navalny. com/platform/, accessed 05 December, 2019.

コメント